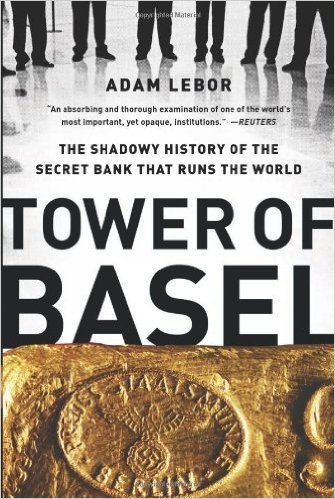

Despite the rather sensational blurb, Tower of Basel manages to be a somewhat clear-headed expose of the somewhat obscure but highly influential Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

The BIS is one of those unknown international institutions that no one seems to really know about. Yet, it has played a subtly significant role in shaping the international financial and regulatory landscape of the post WWII world. It is a bank owned by central banks, that performs financial services for these banks. It is a forum where central bankers the world over meet for sumptuous dinners, play golf with each other, and swap stories, all in the utmost discretion.

In the book, Lebor lays out the surprisingly engaging history of the BIS, from its origins as an institution for facilitating German reparations after WWI, to the pivotal role it played in European integration and monetary union and its growth into a global financial institution and a hub of research and analysis.

But an institution like the BIS is no stranger to skeletons in the closet. Lebor goes into quite some detail about how the BIS became a tool for the Nazi-controlled Reichsbank. It authorised the transfer of BIS’ holdings of Czechoslovakia’s gold reserves to the Nazi coffers after the former’s annexation by the latter. During the war, it accepted looted gold from the Nazis as a form of payment for the latter’s debt obligations under the Young Plan.

After the war, the Bretton Woods Conference recommended that BIS be liquidated, but it survived this existential crisis and went on to shape itself to the needs of the postwar financial world. Over the ensuing decades, it built up a name and reputation for itself as a respected nexus for financial regulators and played a part in setting international financial regulations, all in the name of monetary stability. The BIS pushed strongly for European integration and the formation of a monetary union under a single currency. During the Eurozone crisis, the BIS holds partial responsibility for coordinating the tough austerity measures that some argue have made the crisis worse.

As an institution, the BIS is simultaneously a private bank and an outsized influence on financial systems and regulatory frameworks. This opens up manifold opportunities for conflicts of interest between its two roles – as a profit maximizer and as a regulator. Protected by a swathe of legal immunities and enjoying the patronage of powerful central banks, the BIS has considerable regulatory fiat, unencumbered by democratic accountability.

These are the qualities with which Lebor takes issue. From Lebor’s perspective, the BIS’ non-transparent, anti-democratic, and elitist nature has no place in the 21st century. After the 2008 financial crisis, with calls to break up large unwieldy banks with too much buying power, the BIS’ looming presence seems even more of an anachronism, vesting disproportionate amounts of influence on global markets in the hands of a few powerful and well-fed men.

In making this case, Lebor points to the various indiscretions that the BIS perpetrated with respect to its actions in World War 2, which were in part made possible by its legally protected, supranational nature. He also points to the tottering European integration project, spearheaded by the BIS, as emblematic of the split incentives of the bank – that the bank, influenced by certain factions within it, would push for financial regulatory arrangements in the Eurozone that would favor certain countries over others.

An interesting perspective that is introduced in the book is the notion of Nazi leadership continuity in the German financial sphere following the war, exemplified by the likes of Karl Blessing and Herman Abs, former Nazi party members who took up influential leadership positions in Germany after the war. Lebor’s implication that the essential German realpolitik imperatives have not really changed with respect to Europe, and that it pushed, through the BIS, the notion of European integration at least partly for self-serving ends – the creation of a large European market to service German exports.

I don’t know enough about the historical literature to make comments about the positioning of Lebor’s allegations on European integration and the role of the BIS in the post-war regime. But I can say that Lebor has written here an intriguing and perhaps contentious tract, one that makes substantive comments about a secretive and unaccountable institution, but in doing so, does not descend into polemics. If anything, reading it has been an edifying introduction into a little-known part of the international network of institutions.

I give this work: 4 out of 5 gold standards